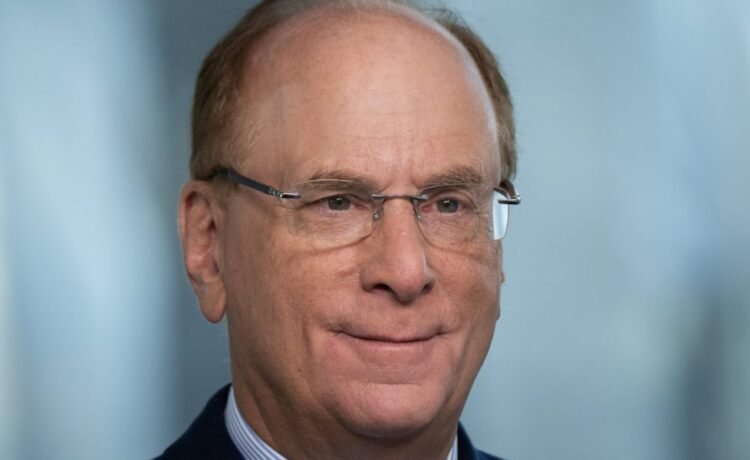

To Larry Fink, CEO of $90 trillion asset manager BlackRock, the economy’s biggest worry isn’t high inflation or a possible recession: it’s a lack of hope. More specifically, it’s about how millennials and Gen Z just don’t trust boomers after looking at what they’ve done to the economy. And you know, what, he says: They’re right.

In his annual letter to BlackRock shareholders released Tuesday, Fink sounded alarmed as he looked back on his parents’ retirement situation, his own generation’s expectations of retirement, and what lies ahead for the young workers who have to shoulder the load. And he said he was stunned by one particular fact about Gen Z.

Fink cited a recent finding by a long-running University of Michigan survey that tracks 12th graders’ public sentiment. Compared with 20 years ago, it found “the current cohort of young Americans is 50% more likely to question whether life has a purpose. Four-in-10 say it’s “hard to have hope for the world.’” It’s the worst result since 1976, the Wall Street Journal reported. Let that sink in, Fink writes: “I’ve been working in finance for almost 50 years. I’ve seen a lot of numbers. But no single data point has ever concerned me more than this one.”

Fink pointed to the retirement system as a key flashpoint. As the nation’s demographics trend older and more Americans live longer, Social Security and other retirement benefit plans are struggling to keep up—and so far, nobody’s been willing to make the massive changes required to make sure that young workers will be able to collect their benefits once they reach retirement age.

As Fink sees it, the blame for the retirement crisis—and, by association, Gen Z’s general malaise about their economic futures—sits squarely on the shoulders of his generation. As Baby Boomers have continued to kick the retirement-reform can down the road, they’ve lost the trust of younger Americans, who can already foresee that they’ll be left to deal with the consequences.

“[Young people] believe my generation — the Baby Boomers — have focused on their own financial well-being to the detriment of who comes next,” Fink wrote. “And in the case of retirement, they’re right.”

The audacity of hope

Fink pointed out that the retirement crisis isn’t as far away as many people think. The Social Security Administration has said it won’t have enough money to pay people their full benefits as soon as 2034. Even as new medical treatments, including drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy, help people live longer, the retirement age isn’t budging to make up for all those extra years of collecting benefits.

“No one should have to work longer than they want to. But I do think it’s a bit crazy that our anchor idea for the right retirement age — 65 years old — originates from the time of the Ottoman Empire,” Fink wrote. “As a society, we focus a tremendous amount of energy on helping people live longer lives. But not even a fraction of that effort is spent helping people afford those extra years.”

Fink pointed out that the Netherlands started raising the retirement age to correspond with rising life expectancy a decade ago, and Japan has been enacting policies to boost its labor participation rate since the early 2000s. He didn’t go so far as to explicitly advocate for increasing the retirement age, but Fink’s message is clear: something needs to budge.

Retirement is just one piece of the puzzle. When it comes to the economy at large, Fink’s biggest fear is fear itself—specifically, young Americans’ growing lack of confidence about putting their money in capital markets. Fink wrote that he sees popular confidence in investing as a key factor in America’s historical success as a nation.

Whereas other countries have struggled to convince citizens that putting their money to work by investing it is just as safe as keeping it in cash, Americans have historically been much more trusting of capital markets. That’s been a key driver of economic growth and American supremacy on the global stage. Fink observes that that trust is waning, especially among young Americans—and that risks costing the country its economic identity.

“Hope has been the nation’s greatest economic asset … If future generations don’t feel hopeful about this country and their future in it, then the U.S. doesn’t only lose the force that makes people want to invest. America will lose what makes it America,” Fink wrote. “Without hope…we risk becoming a country where people keep their money under the mattress and their dreams bottled up in their bedroom.”

Fortune recently reported that the U.S. is one of just four countries where young people report being significantly less happy than older citizens, per World Happiness Project data. A post-pandemic surge in social anxiety, on top of a nationwide cost of living crisis, has soured many young adults’ views on the economy. This collides with the fact that their wallets are collectively pretty full: New York Fed data shows that Gen Z and Millennials have grown their collective wealth by 80% in the past four years, while still trailing well behind boomers.

Fink argues that the solution to the confidence crisis gripping the economy for his generation to give up some control, and listen to their younger counterparts—the future leaders who will be left to clean up the broken retirement system.

“How do we get our hope back? … Any answer has to start by bringing young people into the fold,” Fink wrote. “Young people have lost trust in older generations. The burden is on us to get it back. And maybe investing for their long-term goals, including retirement, isn’t such a bad place to begin.”