Although Carr was the first woman and the first Black person to run NCES, her “firsts” go back decades. She joined NCES in 1993, after teaching statistics at Howard University and a stint as a statistician in the Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights. “I was the first person of color in NCES to ever have a managerial job, period,” said Carr. She broke a long record: The education statistical agency dates back to 1867, created in the aftermath of the Civil War as part of an effort to help the South recover during Reconstruction. She was appointed commissioner by former President Joe Biden in 2021.

“It’s a kill-the-messenger strategy,” she said. “We have just been the messenger of how students in this country are faring.”

Congress established a six-year term for the commissioner so that the job would straddle administrations and insulate statistics from politics. Carr’s term was supposed to extend through 2027, but she made history with yet another first: the first NCES commissioner to be fired by a president.

Carr wasn’t thinking about her gender or her race, despite the fact that three days earlier, Trump had abruptly fired another Black senior official, Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr., the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. “Maybe they found out I was the only Biden appointee left in the department,” Carr said. “Maybe they didn’t realize that until then.”

Carr has reason to be puzzled by her firing. She is hardly a radical. She defended standardized tests against charges that they are racist. She publicly made the case that the nation needs to pay attention to achievement gaps, even if it sometimes means putting a spotlight on the low achievement of Black and Hispanic students. “The data can reveal things about what people can do to improve it,” Carr said.

She was dismissed on Feb. 24, more than a week before Education Secretary Linda McMahon’s Senate confirmation on March 3. The department named Carr’s deputy, Chris Chapman, to act as her replacement, but subsequently fired him in a round of mass layoffs on March 11. The agency was then leaderless until July 7, when another senior department official was told to add NCES to his responsibilities.

Civil servant

In January, at the start of the second Trump administration, Carr thought her job was relatively safe. As a career civil servant, she’d worked with many Republican administrations and served as second in command under James “Lynn” Woodworth, whom Trump appointed as NCES commissioner in his first term. Both Woodworth and Carr say they had a good working relationship because they both cared about getting the numbers right. Indeed, Woodworth was so troubled and disturbed by Carr’s dismissal and the fate of the nation’s education statistics agency that he spoke out publicly, risking retaliation.

Even Carr’s fiercest critics, who contend she was an entrenched bureaucrat who failed to modernize the statistical service and allowed costs to balloon, condemned the humiliating way she was dismissed.

“She deserves the nation’s gratitude and thanks” for setting up a whole system of assessments, said Mark Schneider, who served as the director of the Institute of Education Sciences (IES), which oversees NCES, from 2018 to 2024 and as NCES commissioner from 2005 to 2008.

A landing team

The transition seemed normal at first. A “landing team” — emissaries from the Trump transition team — arrived in mid-January and Carr briefed them three times. They asked questions about NCES’s statistical work. “They were quite pleasant, to be honest,” Carr said. “They seemed curious and interested.”

“But that was before DOGE got there,” she said.

Carr released the 2024 Nation’s Report Card on Jan. 29. More students lacked the most basic reading and math skills. It was front-page news across the nation.

Days later, DOGE arrived. Still, Carr wasn’t worried. “We actually thought we were going to be OK,” Carr said. “We thought that their focus was going to be on grants, not contracts.”

The Institute of Education Sciences had awarded millions of dollars in grants to professors and private-sector researchers to study ways to improve diversity and equity in the classroom — priorities that were now out of favor with the Trump team. Carr’s agency is housed under the IES umbrella, but Carr’s work didn’t touch upon any of that.

However, NCES has an unusual structure. Unlike other statistics agencies, NCES has never had many statisticians on staff and didn’t do much in-house statistical work. Because Congress put restrictions on its staffing levels, NCES had to rely on outside contractors to do 90 percent of the data work. Only through outside contractors was the Education Department able to measure academic achievement, count students and track university tuition costs. Its small staff of 100 primarily managed and oversaw the contracts.

Keyword searches

Following DOGE instructions, Carr’s team conducted keyword searches of DEI language in her agency’s contracts. “Everyone was asked to do that,” she said. “That wasn’t so bad. The chaotic part really started when questions were being asked about reductions in the contracts themselves.”

Carr said she never had direct contact with anyone on Musk’s team, and she doesn’t even know how many of them descended upon the Education Department. Her interaction with DOGE was secondhand. Matthew Soldner, acting director of IES, summoned Carr and the rest of his executive team to his office to respond to DOGE’s demands. “We met constantly, trying to figure out what DOGE wanted,” Carr said. DOGE’s orders were primarily transmitted through Jonathan Bettis, an Education Department attorney, who was experienced with procurement and contracts. It was Bettis who talked directly with the DOGE team, Carr said.

The main DOGE representative who took an interest in NCES was “Conor.” “I don’t know his last name,” said Carr. “My staff never saw anyone else but Conor if they saw him at all.” Conor is 32-year-old Conor Fennessy, according to several media reports. His deleted LinkedIn profile said he has a background in finance. (Fennessy has also been involved in getting access to data at Health and Human Services and spearheading cuts at the National Park Service, according to media reports.) Efforts to reach Fennessy through the Education Department and through DOGE were unsuccessful.

“It was chaotic,” said Carr. “Bettis would tell us what DOGE wanted, and we ran away to get it done. And then things might change the next day. ‘You need to cut more.’ ‘I need to understand more about what this contract does or that contract does.’”

It was a lot. Carr oversaw 60 data collections, some with multiple parts. “There were so many contracts and there were hundreds of lines on our acquisition plans,” she said. “It was a very complex and time-consuming task.”

Lost in translation

The questions kept coming. “It was like playing telephone tag when you have complicated data collections and you’re trying to explain it,” Carr said. Bettis “would sometimes not understand what my managers or I were saying about what we could cut or could not cut. And so there was this translation problem,” she said. (Efforts to reach Bettis were unsuccessful.) Eventually a couple of Carr’s managers were allowed to talk to DOGE employees directly.

Carr said her staff begged DOGE not to cut a technology platform called EDPass, which is used by state education agencies to submit data to the federal Education Department on everything from student enrollment to graduation rates. For Carr, EDPass was a particular point of pride in her effort to modernize and process data more efficiently. EDPass slashed the time it took to release data from 20 months in 2016-17 to just four months in 2023-24.

Carr said DOGE did not spare EDPass. Indeed, DOGE did not spare much of NCES.

On Feb 10, only about a week after DOGE arrived, Carr learned that 89 of her contracts were terminated, which represented the vast majority of the statistical work that her agency conducts. “We were in shock,” said Carr. “What do you mean it’s all gone?”

Even its advocates concede that NCES needed reforms. The agency was slow to release data, it used some outdated collection methods and there were places where costs could be trimmed. Education Department spokesperson Madi Biedermann said that the department, “in partnership with DOGE employees,” found contracts with overhead and administrative expenses that exceeded 50 percent, “a clear example of contractors taking advantage of the American taxpayer.”

Piloting an old airplane

Carr said she was never a fan of the contracting system and wished she could have built an in-house statistical agency like those at the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But that would have required congressional authorization for the Education Department to increase its headcount. That never happened. Carr was piloting an old airplane, taped together through a complicated network of contracts, while attempting to modernize and fix it. She said she was trying to follow the 2022 recommendations of a National Academies panel, but it wasn’t easy.

The chaos continued over the next two weeks. DOGE provided guidelines for justifying the reinstatement of contracts it had just killed and Carr’s team worked long hours trying to save the data. Carr was particularly worried about preserving the interagency agreement with the Census Bureau, which was needed to calculate federal Title I allocations to high-poverty schools. Those calculations needed to be ready by June and the clock was ticking.

Her agency was also responsible for documenting geographic boundaries for school districts and classifying locales as urban, rural, suburban or town. Title I allocations relied on this data, as did a federal program for funding rural districts. “My staff was panicking,” said Carr.

The DOGE sledgehammer came just as schools were administering an important international test — the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). The department was also in the midst of a national teachers and principals survey. “People were worried about what was going to happen with those,” said Carr.

Even though DOGE terminated the PISA contract, the contractor continued testing in schools and finished its data collection in June. But now it’s unclear who will tabulate the scores and analyze them. The Education Department disclosed in a June legal brief that it is restarting PISA. “I was told that they’re not going to do the national report, which is a little concerning to me,” Carr said. Asked for confirmation, the Education Department did not respond.

Another widely used data collection, the Early Childhood Longitudinal Survey (ECLS-K 2024), which tracks a cohort of students from kindergarten through elementary school, was supposed to collect its second year of data as the kindergarteners progressed to first grade. “We had to give up on that,” said Carr.

NAEP anxiety

Carr said that behind the scenes, her priority was to save NAEP. DOGE was demanding aggressive cuts, and she worked throughout the weekend of Feb. 22-23 with her managers and the NAEP contractors to satisfy the demands. “We thought we could cut 28 percent — I even remember the number — without cutting into critical things,” she said. “That’s what I told them I could do.”

DOGE had been demanding 50 percent cuts to NAEP’s $185 million budget, according to several former Education Department employees. Carr could not see a way to cut that deep. The whole point of the exam is to track student achievement over time, and if too many corners were cut, it could “break the trend,” she said, making it impossible to compare the next test results in 2026 with historical scores.

“I am responsible in statute and I could not cut NAEP as much as they wanted to without cutting into congressionally mandated activities,” Carr said. “I told them that.”

While Carr and DOGE remained far apart in negotiations over cost, a security officer appeared at her office door at 3:50 p.m. on Feb. 24. Carr remembers the exact time because colleagues were waiting at her door to join her for a 4 p.m. Zoom meeting with the chair of the board that oversees NAEP.

The security officer closed the door to her office so he could tell her privately that he was there to escort her out. He said she had 15 minutes to leave. “Escort me where? What do you mean?” Carr asked. “I was in shock. I wasn’t even quite understanding what he was asking, to be honest.”

The security officer told her about an email saying she was put on administrative leave. Carr checked her inbox. It was there, sent within the previous hour.

The security officer “was very nice,” she said. “He refused to call me Peggy,” and addressed her as Dr. Carr. “He helped me collect my things, and I left.” He opened the doors for her and walked her to her car.

“I had no idea that this was going to happen, so it was shocking and unexpected,” Carr said. “I was working like I do every other day, a busy day where every minute is filled with something.”

She said she’s asked the department why she was dismissed so abruptly, but has not received a response. The Education Department said it does not comment to the public on its personnel actions.

Packing via Zoom

Two days later, Carr returned to pick up other belongings. Via Zoom, Carr’s staff had gone through her office with her — 35 years worth of papers and memorabilia — and packed up so many boxes that Carr had to bring a second car, an SUV.

When Carr and her husband arrived, she said, “there were all these people waiting in the front of the building cheering me on. The men helped me put the things in my husband’s car and my car. It was a real tearjerker. And that was before they would be dismissed. They didn’t know they would be next.”

Less than two weeks later, on March 11, most of Carr’s staff — more than 90 NCES staffers — was fired. Only three remained. “I thought maybe they just made a mistake, that it was going to be a ‘whoops moment’ like with the bird flu scientists or the people overseeing the weapons arsenal,” Carr said.

The fate of NCES remains uncertain. The Education Department says that it is restarting and reassessing some of the data collections that DOGE terminated, but the scope of the work might be much smaller. Carr says it will take years to understand the full extent of the damage. Carr was slated to issue a statement about her thoughts on NCES on July 14.

The damage

The immediate problem is that there aren’t enough personnel to do the work that Congress mandates. So far, NCES has missed an annual deadline for delivering a statistical report to Congress — a deadline NCES had “never, ever missed” in its history, Carr said — and failed to release the 2024 NAEP science test scores in June because there was no commissioner to sign off on them. But the department managed to calculate the Title I allocations to high-poverty schools “in the nick of time,” Carr said.

In addition to the collection of fresh data, Carr is concerned about the maintenance of historical datasets. When DOGE canceled the contracts, Carr counted that NCES had 550 datasets scattered in different locations. NCES doesn’t have its own data warehouse and Carr was trying to corral and store the datasets. She’s worried about protecting privacy and student confidentiality.

An Education Department official said that this data is safe and will soon be transferred to IES’s secure servers.

In the meantime, Carr says she plans to stay involved in education statistics — but from the outside. “With this administration wanting to push education down to the states, there are opportunities that I see in my next chapter,” Carr said. She said she’s been talking with states and school districts about calculating where they rank on an international yardstick.

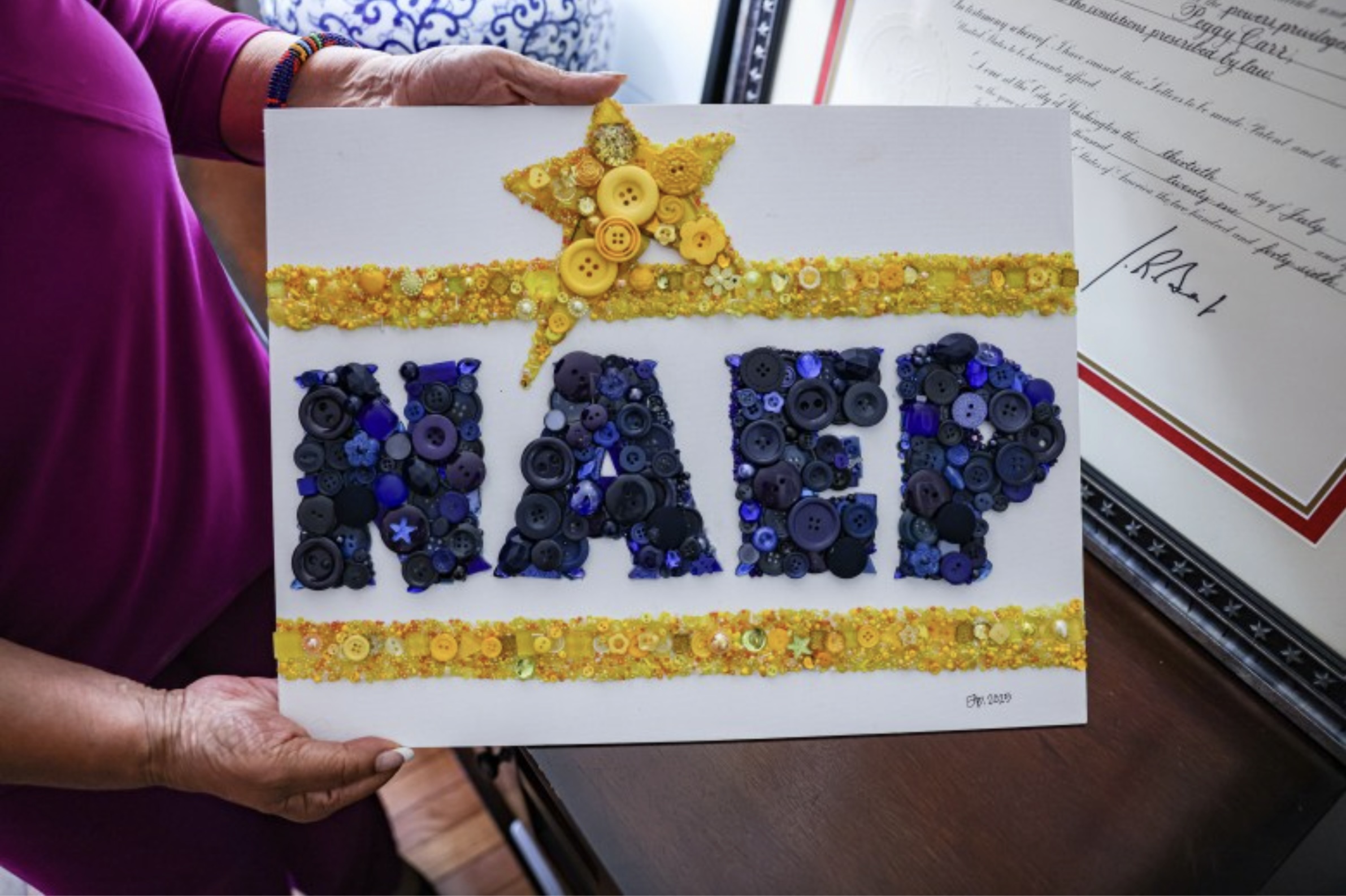

Carr is in close touch with her former team. In May, 50 of them gathered at a church in Virginia to commiserate. A senior statistician gave Carr a homespun plaque of glued blue buttons spelling the letters NAEP with a shiny gold star above it. It was a fitting gift. NAEP is regarded as the best designed test in the country, the gold standard. Carr built that reputation, and now it has gone home with her.

Contact staff writer Jill Barshay at 212-678-3595, jillbarshay.35 on Signal, or barshay@hechingerreport.org.