Capin led an 11-member team that gathered 66 studies in which reading instruction was observed in real classrooms over the past 40 years. Most of the studies took place after 2000 and included observations of almost 1,800 teachers. The studies not only looked at reading or English language arts classes, but also science and social studies. In some of the studies, researchers recorded hours of instruction and analyzed transcripts.

These observations and recordings are just snapshots of what is happening in classrooms. Unfortunately, these observational studies can’t explain why teachers aren’t following the scientific evidence for reading comprehension, and Capin was unable to determine if comprehension instruction had improved most recently with new interest in the science of reading. But he shared a few insights.

Little time spent on reading

Teachers spend limited time reading texts with children. “The obvious problem is that it’s hard to support reading comprehension if students are not reading,” said Capin.

The dearth of reading was especially pronounced in science classes where teachers tended to prefer PowerPoint slides over texts. More time was spent on reading comprehension instruction in reading or English class, but it was still just 23 percent of instructional time. Still, that is a big improvement over the original 1978 study, which documented that only 1 percent of instructional time was spent on reading comprehension.

A separate survey of middle school teachers published in 2021 echoes these observational findings that very little reading is taking place in classrooms. Seventy percent of science teachers said they spent less than 6 minutes on texts a day, or less than 30 minutes a week. Only 50 percent of social studies teachers said they spent more time reading in classrooms.

“It’s possible that poor reading instruction may beget poor reading instruction,” said Capin. “Teachers frequently report that their students have difficulties reading grade-level texts.” So they avoid reading altogether.

It can seem like a catch-22. Teachers don’t devote more time to reading instruction because students have difficulty reading. But without more time reading, students cannot improve.

More attention to decoding than comprehension

Capin said his team found that reading instruction was more focused on word reading skills, what educators call “decoding.” Researchers noticed that teachers were also building students’ knowledge, especially in science and social studies classes. But this knowledge building was mostly divorced from engaging students in text comprehension.

“We took this approach that reading comprehension instruction is defined by reading and understanding text,” said Capin. That might sound obvious, but Capin said that some advocates of knowledge building criticized his analysis, arguing that knowledge building alone is beneficial for reading comprehension and it doesn’t matter if the teacher uses slides or actual texts.

Low-level instruction

Evidence-based reading instruction, as recommended in teaching guides by the Institute of Education Sciences, is rare, Capin said.

Instead, researchers observed “low-level” reading instruction in which a teacher asks a question and students respond with a one-word answer. Capin offered me an example.

Teacher: We just read about ancient Egypt. Who were the ancient Egyptian leaders?

Class: Pharaohs!

And the teacher moves on.

A more sophisticated approach might be to ask students about the goals of the pharaohs, or why ancient Egyptians built the tombs.

Teachers tended to confirm whether student responses were “right” or “wrong.” Capin said that only 18 percent of teacher responses elaborated on or developed students’ ideas.

Capin said teachers tended to lecture rather than encourage students to talk about what they understand or think. Teachers often read the text aloud, asked a question and then answered the question themselves when students didn’t answer it correctly. He said that leading a discussion might help students better understand the text.

Capin said teachers also often ask generic comprehension questions, such as “What is the main point?” without considering whether the questions are appropriate for the reading passage at hand. For example, in fiction, the author’s main point is not nearly as important as identifying the main characters and their goals. Even evidence-based ways of improving reading comprehension can be poorly executed.

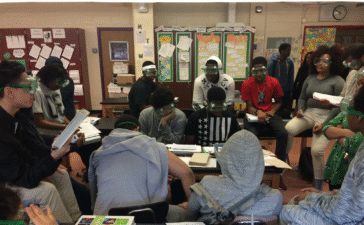

Some teachers are leading reading discussions in their classrooms. Capin said he visited one such classroom a few weeks ago. But he thinks good comprehension instruction isn’t commonplace because it’s much harder than teaching foundational reading skills. Teachers have to fill in gaps in students’ skills and background knowledge so that everyone can engage. Teacher training programs don’t put enough emphasis on evidence-based methods, and researchers aren’t good at telling educators about these methods. Meanwhile, teachers face pressures to produce high test scores and low-level comprehension strategies can yield short-term results.

“I also don’t want to pretend that researchers know it all when it comes to reading comprehension instruction,” said Capin. “We are about 20 years behind in the science of reading comprehension instruction compared to foundational reading skills.”

Interest in the science of reading has been exploding around the country over the past five years, especially since a podcast, “Sold a Story,” highlighted the need for more phonics instruction. Hopefully, we won’t have to wait another 50 years for comprehension to get better.