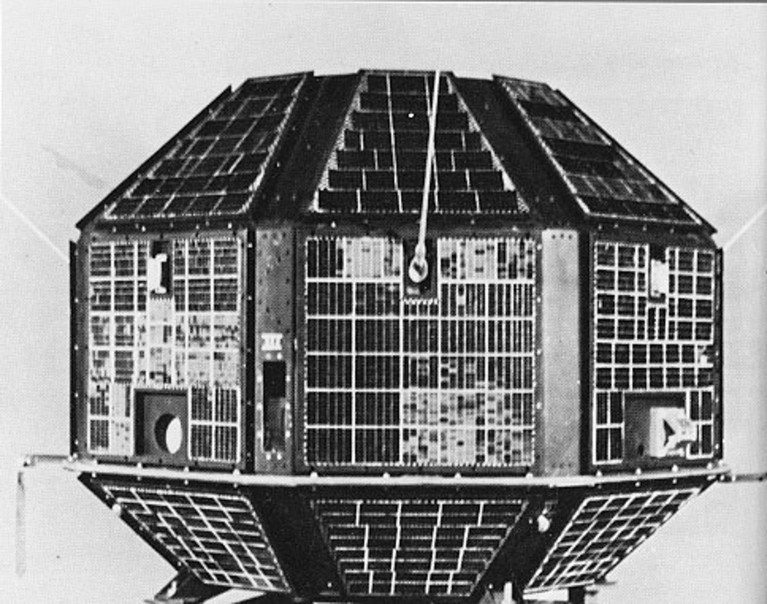

The satellite, Aryabhata, provided a huge boost to India’s space programme.Credit: NASA/Alamy

In the early hours of 19 April 1975, the mood at the Soviet military launch site of Kapustin Yar — a space test facility north of the Caspian Sea — was heavy with anticipation. Scientists and engineers moved with brisk deliberation, the pre-launch silence was punctuated only by the rustle of paper, the clicking of relays and the careful exchange of words in thick Russian and Indian accents.

The Indian engineers, most of whom were less than 35 years old, had arrived at this remote enclave in what is now southern Russia to hurl their nation’s first satellite, named Aryabhata after an ancient Indian astronomer, into space, with the help of a Kosmos-3M launch vehicle. The relatively light satellite — a 358-kilogram payload packed with scientific instruments — had been flown halfway across the continent in a custom-built shockproof container padded with helical springs, designed to shield it from any forces it wouldn’t be able to endure.

Space debris is falling from the skies. We need to tackle this growing danger

When Aryabhata arrived at the Kapustin Yar cosmodrome, its constituent parts — bottom shell, instrumentation deck and top shell — were reassembled and carefully inspected. Soviet scientists meticulously checked the satellite’s shock resistance, thermal cycles and vibration. To their surprise, it passed the tests with flying colours.

At the time, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) was still a young agency with limited experience. For many of the 200-odd scientists and engineers at what was then the ISRO Satellite Centre in Bengaluru, India, the moment marked their first real encounter with orbital space flight. Although they had previously worked on sounding rockets and small collaborative projects, nothing matched the scale or importance of this mission. The modest polyhedral satellite was about to redefine what a low-income country could accomplish.

When the Kosmos-3M rocket roared to life, it carried not just circuitry but also the dreams of a nation not even 30 years free from colonial rule. The launch was a success. As Aryabhata hurtled through layers of piercing cold Soviet air, a space programme destined to become the envy of the world, for its ability to operate on a shoestring budget was quietly born.

Fifty years on, ISRO provides launch services to other low- and middle-income countries, nurturing the space ambitions of many African and Latin American nations. With private for-profit enterprises increasingly dominating the space industry, Aryabhata’s legacy offers a valuable counterpoint.

India’s space programme showcases the value of public investment in science. The nation’s space-related technology has contributed to the development of ultralightweight artificial limbs, health–care devices and water-purification systems, for instance. Perhaps Aryabhata’s more immeasurable impact, however, is the boost it has given to national confidence — inspiring a generation of scientists and engineers. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that Aryabhata did not just orbit Earth, it orbited India’s imagination.

Scientific modernity

Aryabhata was never meant to dazzle as a payload. Its purpose was humble but profound: to provide hands-on experience in designing, building and operating a spacecraft to a team of young Indian scientists. Its solar panels were modest, its instruments sparse and its spin-stabilization system rudimentary. Yet, all of the spacecraft’s components, from its telemetry boards to its thermal insulation, were made in India.

The decision to go low-tech was intentional. U. R. Rao, the project’s director, had convinced ISRO’s leadership that developing operational communications and remote-sensing satellites was impossible without building experimental ones first. The mission served as an orbital classroom. Its main purpose: training a new generation of space technologists and validating home-grown hardware.

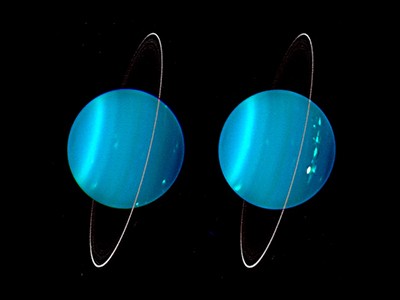

Why the European Space Agency should join the US mission to Uranus

The name of the satellite — Aryabhata — was chosen deliberately. During the initial days of the project, it was called ISRO Satellite-1, or IS-1, internally. The idea to rebrand the spacecraft emerged when then-ISRO chair Satish Dhawan sought then-prime minister Indira Gandhi’s input, because the satellite neared completion and its public launch was imminent. Both ISRO and the government wanted a name that embodied India’s national pride and cultural heritage.

Gandhi saw scientific modernity as an extension of India’s civilizational legacy. After careful consideration, she proposed naming the satellite after the fifth-century mathematician-astronomer Aryabhata, whose pioneering contributions included postulating that Earth rotates on its axis, calculating the value of π to a remarkable precision and laying the foundations of algebra.

The name carried deep symbolism, reaffirming India’s rich history of scientific enquiry and linking ancient intellectual achievements to modern technological progress. Politically, it also provided an alternative narrative to the cold war-era space race between the United States and the Soviet Union by reinforcing India’s unaligned stance. The country was not following global trends, it was merely reclaiming its own long-standing intellectual prowess.

Heartbeat of a nation

With symbolism deeply woven into the project, success was crucial. That’s why, when Aryabhata started tumbling soon after reaching orbit, the engineers who had clustered around consoles at what was then the Sriharikota Range ground station in India held their breath.

The issue was traced to a faulty valve relay that failed to initiate the satellite’s spin, which was crucial for orbital stability. Engineers on the ground sent a correction command and, over four tense days, Aryabhata gathered data on X-ray sources and ionospheric electrons.

India’s space scientists continue to expand their programme and inspire the next generation.Credit: Anshuman Poyrekar/Hindustan Times via Getty

By day five of the mission, another snag was detected. A 9-volt power bus, which powered all three scientific experiments (X-ray astronomy, solar γ-rays and aeronomy), had failed. It was then decided to shut down the experiments and operate Aryabhata as a technological test platform. It was a tough but pragmatic decision. The mission’s main goal had always been to build capability; the scientific experiments were a bonus. Then, on its 45th orbit, the backup spin system kicked in and the satellite steadied at 50 revolutions per minute. Cheers erupted at mission control. With this, India had not only launched but also controlled its first satellite in orbit. Despite the satellite being scientifically extraneous, it continued to transmit data reliably for the next two years.